Submission of Comments to the Draft Law on the procedure for lifting confidentiality of communications

Today, Homo Digitalis’ Legal & Policy Team submitted its comments in the context of the Ministry of Justice’s open consultation on the draft law entitled “Procedure for the lifting of the confidentiality of communications, cybersecurity and protection of citizens’ personal data”

Homo Digitalis welcomes the submission of the present draft of the Draft Law on the Protection of Privacy and Security of Personal Data. Law to regulate the procedure for lifting the confidentiality of communications, including the restructuring of the National Intelligence Service (NIS) and the criminalization of the trade, possession and use of prohibited surveillance software in Chapters B to E of the old draft law. The issues of lifting the confidentiality of communications need clarification to ensure the validity of the procedure and to guarantee the constitutionally guaranteed right to confidentiality of communications (see Article 19 of the Constitution). Although the Bill presents a limited number of positive elements, it is rife with a number of problematic provisions, which we highlight in our comments, and the institutional omission of the inclusion of the DPAA in the legislative process poses significant challenges. Homo Digitalis urges the Ministry of Justice to take seriously the relevant comments of the DPAA on the provisions of this Sect. Law, as posted on its website and in this public consultation. Homo Digitalis drafts these comments in their entirety.

Homo Digitalis also welcomes the amendment of the national regulations for the transposition of Directive 2016/680 in Law 4624/2019 in Chapter F of this Law, which is a consequence of the submission of a relevant complaint before the European Commission by Homo Digitalis in October 2019, and the relevant consultations initiated by the Commission with the Greek State. This revision, although after the expiry of the compliance date set by the European Commission for the Greek State (June 2022), ensures compliance with European Law and safeguards the constitutionally guaranteed right to the protection of personal data (see Article 9A of the Constitution).

You can read all our comments in detail on the Public Consultation website or here.

Interview with Prof. Chris Brummer on cryptocurrencies and international regulatory cooperation

In recent years, cryptocurrencies have significantly grown in popularity, demand and accessibility. New “stablecoins” have emerged as a relatively low-risk asset category for institutional investors, whereas new “altcoins” have attracted retail investors due to their availability on popular fintech platforms.

These developments have amplified some of the risks inherent in the decentralized and immutable nature of the blockchain technology on which cryptocurrencies rely. Indicatively, sunk costs associated with volatility, loss of private keys or theft have become higher, whereas the financing of illicit activities has increasingly been channeled through cryptocurrencies.

We asked Chris Brummer, Professor of International Economic Law at Georgetown University*, to reflect on the importance of international regulation, standardization or regulatory cooperation in mitigating the above risks, and the challenges entailed in seeking to align or harmonize domestic regulatory approaches.

Prof. Brummer began by noting that the major risk of cryptocurrencies from an investment standpoint lies in their relative complexity — “what they are, how they operate, and the value proposition, if any, that any particular cryptoasset provides. Because of this complexity, they are difficult to price, and unscrupulous actors can exploit the relative ignorance of many investors”, Prof. Brummer explained.

As cryptoassets are inherently cross-border financial products, operating on digital platforms, the mitigation of the risks entailed in their increasing circulation and use requires international coordination.

“This could take place through informal guidelines and practices which, though not “harmonizing” approaches, should at least ensure that reforms are broadly moving in the same direction”, Prof. Brummer notes.

Countries have very different risk-reward appetites—which are defined largely by their own experiences

Achieving even a minimal degree of international consensus may nonetheless prove challenging given the existence of significant regulatory constraints at the domestic level. As Prof. Brummer explains, “for one, although the tech may be new, regulators operate within legacy legal systems. And national jurisdictions don’t identify crypto assets in the same way, in part because they identify just what is a “security” differently, and also define key intermediaries differently, from “exchanges” to “banks.” And these definitions can be difficult to modify — in the U.S. it’s in part the result of case law by the Supreme Court, whereas in other jurisdictions it may be defined by national (or in the case of the EU, regional) legislation. Coordination can thus be tricky, and face varying levels of practical difficulty.”

Apart from key differences in existing domestic regulatory structures, there may also be a mismatch in incentives across different jurisdictions. “Countries have very different risk-reward appetites—which are defined largely by their own experiences”, Prof. Brummer explains. “Take for example how cybersecurity concerns have evolved. Japan was one of the most crypto friendly jurisdictions in the world. Its light touch regulatory posture, began to change when its biggest exchange, Coincheck, was hacked, resulting in the theft of NEM tokens worth around $530 million. Following the hack, Japanese regulators required all the exchanges in the country to get an operating license. In contrast, other G20 countries like France have been more solicitous, and have even seen the potential for modernizing their financial systems and gaining a competitive advantage in a fast-growing industry, especially as firms reconsider London as a financial center in the wake of Brexit. Although not dismissive of the risks of crypto, France has introduced optional and mandatory licensing, reserving the latter for firms that seek to buy or sell digital assets in exchange for legal tender, or provide digital asset custody services to third parties.”

Users in different jurisdictions may face different regulatory constraints or enjoy varying degrees of regulatory protection

Another limiting factor of international coordination is the proliferation of domestic and international regulatory authorities. Prof. Brummer observes that “international standard-setters don’t always agree on crypto approaches, and neither do agencies within countries. International standard-setters and influencers themselves have until recently espoused very different opinions, with the Basel Committee less impressed, and the IMF—committed to payments for financial stability, more intrigued. And even within jurisdictions, regulatory bodies can take varying views. In the US, for example, the SEC has at least been seen to be far more wary of crypto than the CFTC; similarly, from an outsider’s perspective, the ECB’s stance has appeared to be more cautious than, say ESMA’s.”

For the time being, international regulatory cooperation appears to be evolving slowly, in light of the limitations listed above by Prof. Brummer. Users in different jurisdictions, even within the EU, may therefore face different regulatory constraints or enjoy varying degrees of regulatory protection. The Bank of Greece, for one, has issued announcements adopting the views of European supervisory authorities warning consumers of the risks of cryptocurrencies, but has yet to adopt precise guidelines. Yet, as stablecoin projects popularized by established commercial actors gain popularity, we may soon begin to see a shift in international regulatory pace, possibly toward a greater degree of convergence.

* Chris Brummer is the host of the popular Fintech Beat podcast, and serves as both a Professor of Law at Georgetown and the Faculty Director of Georgetown’s Institute of International Economic Law. He lectures widely on fintech, finance and global governance, as well as on public and private international law, market microstructure and international trade. In this capacity, he routinely provides analysis for multilateral institutions and participates in global regulatory forums, and he periodically testifies before US and EU legislative bodies. He recently concluded a three-year term as a member of the National Adjudicatory Council of FINRA, an organization empowered by the US Congress to regulate the securities industry.

** Photo Credits: Jinitzail Hernández / CQ Roll Call

Digital Cartels: The Risks, the Role of Big Data, the Possible Measures & the Role of the EU

By Konstantinos Kaouras*

The risks of tacit collusion have increased in the 21st century with the use of algorithms and machine learning technologies.

In the literature, the term “collusion” commonly refers to any form of co-ordination or agreement among competing firms with the objective of raising profits to a higher level than the non-cooperative equilibrium, resulting in a deadweight loss.

Collusion can be achieved either through explicit agreements, whether they are written or oral, or without the need for an explicit agreement, but with the recognition of the competitors’ mutual interdependence. In this article, we will deal with the second form of collusion which is referred to as “tacit collusion”.

The phenomenon of “tacit collusion” may particularly arise in oligopolistic markets where competitors, due to their small number, are able to coordinate on prices. However, the development of algorithms and machine learning technologies has made it possible for firms to collude even in non-oligopolistic markets, as we will see below.

Tacit Collusion & Pricing Algorithms

Most of us have come across pricing algorithms when looking to book airline tickets or hotel rooms through price comparison websites. Pricing algorithms are commonly understood as the computational codes run by sellers to automatically set prices to maximise profits.

But what if pricing algorithms were able to set prices by coordinating with each other and without the need for any human intervention? As much as this sounds like a science fiction scenario, it is a real phenomenon observed in digital markets, which has been studied by economists and has been termed “algorithmic (tacit) collusion”.

Algorithmic tacit collusion can be achieved in various ways as follows:

- Algorithms have the capability “to identify any market threats very fast, for instance through a phenomenon known as now-casting, allowing incumbents to pre-emptively acquire any potential competitors or to react aggressively to market entry”.

- They increase market transparency and the frequency of interaction, making the industries more prone to collusion.

- Algorithms can act as facilitators of collusion by monitoring competitors’ actions in order to enforce a collusive agreement, enabling a quick identification of ‘cartel price’ deviations and retaliation strategies.

- Co-ordination can be achieved in a sort of “hub and spoke” scenario where competitors may use the same IT companies and programmers for developing their pricing algorithms and end up relying on the same algorithms to develop their pricing strategies. Similarly, a collusive outcome could be achieved if most companies were using pricing algorithms to follow in real-time a market leader (tit-for-tat strategy), who in turn would be responsible for programming the dynamic pricing algorithm that fixes prices above competitive level.

- “Signaling algorithms” may enable companies to automatically set very fast iterative actions, such as snapshot price changes during the middle of the night, that cannot be exploited by consumers, but which can still be read by rivals possessing good analytical algorithms.

- “Self-learning algorithms” may eliminate the need for human intermediation, as using deep machine learning technologies, the algorithms may assist firms in actually reaching a collusive outcome without them being aware of it.

Algorithms & Big Data: Could they Decrease the Risks of Collusion?

Big Data is defined as “the information asset characterized by such a high volume, velocity and variety to require specific technology and analytical methods for its transformation into value”.

It can be argued that algorithms which constitute a “well defined computational procedure that takes some value, or set of values, as input and produces some value, or set of values, as outputs” can provide the necessary technology and analytical methods to transform raw data into Big Data.

In data-driven ecosystems, consumers can outsource purchasing decisions to algorithms which act as their “digital half” and/or they can aggregate in buying platforms, thus, strengthening their buyer power.

Buyers with strong buying power can disrupt any attempt to reach terms of coordination, thus making tacit collusion an unlikely outcome. In addition, algorithms could recognise forms of co-ordination between suppliers (i.e. potentially identifying instances of collusive pricing) and diversify purchasing proportions to strengthen incentives for entry (i.e. help sponsoring new entrants).

Besides pure demand-side efficiencies, “algorithmic consumers” also have an effect on suppliers’ incentives to compete as, with the help of pricing algorithms, consumers are able to compare a larger number of offers and switch suppliers.

Furthermore, the increasing availability of online data resulting from the use of algorithms may provide useful market information to potential entrants and improve certainty, which could reduce entry costs.

If barriers to entry are reduced, then collusion can hardly be sustained over time. In addition, algorithms can naturally be an important source of innovation, allowing companies to develop non-traditional business models and extract more information from data, and, thus, lead to the reduction of the present value of collusive agreements.

Measures against Digital Cartels and the Role of the EU

Acknowledging that any measures against algorithmic collusion may have possible effects on competition, competition authorities may adopt milder or more radical measures depending on the severity and/or likelihood of the risk for collusion.

To begin with, they may adopt a wait-and-see approach conducting market studies and collecting evidence about the real occurrence of algorithmic pricing and the risks for collusion.

Where the risk for collusion is medium, they could possibly amend their merger control regime lowering their threshold of intervention and investigating the risk of coordinated effects in 4 to 3 or even 5 to 4 mergers.

In addition, they could regulate pricing algorithms ex ante with some form of notification requirement and prior analysis, eventually using the procedure of regulatory sandbox.

Such prior analysis could be entrusted to a “Digital Clearing House”, a voluntary network of contact points in regulatory authorities at national and EU level who are responsible for regulation of the digital sector, and should be able to analyze the impact of pricing algorithms on the digital rights of users.

At the same time, competition authorities could adopt more radical legislative measures by abandoning the classic communications-based approach for a more “market-based” approach.

In this context, they could redefine the notion of “agreement” in order to incorporate other “meetings of minds” that are reached with the assistance of algorithms. Similarly, they could attribute antitrust liability to individuals who benefit from the algorithms’ autonomous decisions.

Finally, where the risk for collusion is serious, competition authorities could either prohibit algorithmic pricing or introduce regulations to prevent it, by setting maximum prices, making market conditions more unstable and/or creating rules on how algorithms are designed.

However, given the possible effects on competition, these measures should be carefully considered.

Given most online companies using pricing algorithms operate beyond national borders and the EU has the power to externalize its laws beyond its borders (a phenomenon known as “the Brussels effect”), we would suggest that any measures are taken at EU-wide level with the cooperation of regulatory authorities who are responsible for regulation of the digital sector.

Harmonised rules at EU Regulation level such as the recently adopted General Data Protection Regulation are important to protect the legitimate interests of consumers and facilitate growth and rapid scaling up of innovative platforms using pricing algorithms.

It is worth noting that, following a proposal of the European Parliament, the European Commission is currently carrying out an in-depth analysis of the challenges and opportunities in algorithmic decision-making, while in April 2019, the High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI), set up by the European Commission, presented Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, in which it was stressed that AI should foster individual users’ fundamental rights and operate in accordance with the principles of transparency and accountability.

In conclusion, given the potential benefits of algorithms, but also the risks posed by the creation of “digital cartels”, it is clear that a fine balance must be struck between adopting a laissez-faire approach, which can be detrimental for consumers, and an extremely interventionist approach, which can be harmful for competition.

* Konstantinos Kaouras is a Greek qualified lawyer who works as a Data Protection Lawyer at the UK’s largest healthcare charity, Nuffield Health. He is currently pursuing an LLM in Competition and Intellectual Property Law at UCL. He has carried out research on the interplay between Competition and Data Protection Law, while he has a special interest in the role of algorithms and Big Data.

Bibliography

Lianos I, Korah V, with Siciliani P, Competition Law Analysis, Cases, & Materials (OUP 2019)

OECD, ‘Algorithms and Collusion: Competition Policy in the Digital Age’ (2017)

OECD, ‘Big Data: Bringing Competition Policy to the Digital Era – Background Note by the Secretariat’ (2016)

Deploying DP3T in the real world - how ready are we?

Undoubtably, there has been a big debate in the last couple of months around the topic of contact tracing apps. This debate focuses mainly on the choice of either centralized or decentralized architecture, in order to minimize the processing of personal data and make sure that privacy of participants is protected.

The teams still remaining in the PEPP-PT consortium are perhaps the main representatives of the centralized approach, having published the specifications of ROBERT on April 18, and of NTK the day after. On the other side, the teams in the DP3T consortium criticize centralized systems, pointing out that they can be turned into mass surveillance instruments of governments, and they emphasize on the development of the decentralized model DP3T. However, there have been several studies criticizing the privacy protection offered by decentralized models as well. In the decentralized approaches we should also include the protocol from Apple and Google, which will be soon in the OS of our mobile phones.

Understandably, all these discussions have created a lot of confusion to non-experts. In an effort to clarify some of the issues, we contacted Dr. Apostolos Pyrgelis*, Post-Doctoral researcher in EPFL and member of the DP3T team. In this article we publish his answers on our questions around the DP3T protocol, focusing mainly on how close we are to real-life deployment and the Greek reality. We would like to thank Dr. Apostolos Pyrgelis for his availability.

Also, we would like to thank our member Dr. Ioannis Krontiris** for reaching out to Dr. Apostolos Pyrgelis and the DP3T team and for facilitating this interview. We will soon publish this interview translated in Greek, as well.

1) What is the relation between Google/Apple platform (GACT API) and DP-3T? Is the plan to deploy DP-3T on top of the GACT platform or does it have its own independent access to the OS (e.g. Bluetooth hardware, storage of keys, etc.)?

The DP-3T project is formed by a group of international researchers whose interest is to ensure that proximity tracing technologies will not violate human rights key to our democratic society. It started independently of Google and Apple and remains independent of them. The DP-3T project is constantly making new proposals and is publishing positions to inform the discussion around proximity tracing. These positions may be different from these companies’ strategies or points of view.

The Google/Apple joint system design (i.e., the GACT API) aims at enabling interoperability for decentralized proximity tracing applications across iOS and Android mobile devices. This is particularly important for the success of contact tracing apps. To this end, the plan is to deploy the DP-3T protocol on top of the GACT platform and the DP-3T project has access to a code base for iOS and Android that is functional prior to the corresponding OS upgrades. Currently, DP-3T project members are working in close collaboration with Google/Apple engineers to provide open-source support for their API, since we expect that the majority of national applications will be built on top of it.

2) Broadcasting continuously Bluetooth beacons can be used to track people around, since one could try to link these messages together and create traces. What countermeasures do you take against this?

In the DP-3T system, the users’ mobile devices broadcast to their vicinity (random looking) ephemeral identifiers via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). To prevent user tracking via these broadcasts, the ephemeral identifiers are changing regularly (e.g., every 15 min). We here note that this is a shared feature among DP-3T and the GACT platform.

3) What is your experience and lessons learnt from testing the app with real users? How many manual tracers did you use for these tests?

We here clarify that we did not perform any testing of the application with real users or contact tracers. We only performed field experiments in known scenarios for which we could collect ground truth that would enable us to evaluate the accuracy of using BLE beacons for distance estimation among individuals, in various settings. A brief overview of these experiments can be found on the following video. We are currently processing the results of the field experiments aiming to identify the appropriate configurations and parameters for reliable distance estimation using BLE.

4) What would cause a false positive or a false negative in the DP-3T system? Consider for example thousands of people stuck in traffic in a busy city like Athens. That means I am in my car stopped for several minutes next to someone in their own car who’s infected. What existing measures are being considered to mitigate this class of problems?

First, we remind that traditional, person-based contact tracing has a lot of false positives since the majority of users that are exposed to infected others, do not present symptoms and do not get themselves infected. Similarly, it also has false negatives since infected users are unable to recall all the people that they met with in the recent past or identify strangers that they encountered in a bus, a shop, etc.

It is important to distinguish the above false positives/negatives from those that are related to contact discovery, i.e., the fact that two users were exposed to each other in close distance and for a specific amount of time (as defined by the public health authorities), when it comes to digital contact tracing. In the DP-3T system, the contact discovery process is realized via transmissions over Bluetooth, whose wireless broadcast nature is inherently affected by factors such as physical objects, radio interference, weather conditions, etc. This might lead to contact discovery false positives, e.g., if a contact is registered even though there is clear physical separation, such as a wall, between the users, and false negatives, e.g., if an actual contact is missed due to radio interference. The DP-3T team is currently performing extensive measurements to better understand the performance of Bluetooth communications for distance estimation in various settings and parameterize the application in a very conservative manner such that false positives/negatives are limited. We have not explicitly tested the traffic jam scenario, but to account for such situations the app will allow the users themselves to temporarily disable the contact discovery process.

5) Which factors are affected while deployment of DP-3T is scaled up? Would the protocol scale to the magnitude of millions of users?

The DP-3T protocol is designed in such a way that it easily scales to countries with millions of users without compromising their privacy. User devices need to download from the backend server minimal information per day (a few MBs) — which makes DP-3T also scalable to countries with poor broadband — and require very little time (a few secs) to generate their ephemeral keys and compute the infection risk of their owner.

6) Have you been approached by the Greek authorities regarding deployment of DP-3T in Greece? Do you have any indication in which direction Greece wants to take with respect to contact tracing apps?

We have not been approached by the Greek authorities regarding deployment of DP-3T in their country. As such, we do not have any information about the Greek plans with respect to contact tracing applications.

7) Assuming that Greece opts in for a decentralised solution in the future (DP-3T or other), what information would Greece have to share with other countries regarding visitors and tourists in order to achieve interoperability between decentralised solutions across countries? Would that reveal travel plans of people back to their homelands?

Interoperability of contact tracing systems across countries is a very important factor for their success — especially, in cases of free movement, such as the EU, where people travel daily to other countries for business, leisure, etc. The DP-3T project envisions interoperability between decentralized solutions across countries and is currently collaborating with designers and engineers from various countries to address its technical challenges. In one of the proposed interoperability solutions, users would have to configure their application to receive notifications from the countries that they travel into. Moreover, the homeland backend servers of the infected users would have to forward the relevant data to the backends of other countries that these users have visited. While this would reveal information about users’ travel patterns to their homelands, we believe that this is acceptable for the international success of contact tracing.

8) A major issue for contact tracing apps is persuading people to actually use them. Do you have any indication what is the minimum necessary penetration of the app to the population in order for the app to be effective? Is a high degree of case identification within a population required and does this translate to widespread testing?

Indeed, the success of contact tracing apps depends on users’ adoption and this is why we believe that it is of paramount importance to ensure them that their privacy is protected. While such a large scale deployment has never been performed before it is not clear what is the minimum necessary penetration of the app to the population for it to be successful. However, epidemiologists believe that any percentage of app usage will contribute to the pandemic mitigation efforts. To this end, the DP-3T project is hopeful that the app will have impact for “proximity communities”, e.g., commuters, co-workers, students, that have a suitable density of deployment. Finally, we remark that contact tracing apps should be complementary (and absolutely not a replacement) to traditional interview-based contact tracing and should be combined with public health infection testing policies. What really matters, at the end of the day, is to bring and maintain the virus transmission rate below 1.

* Dr. Apostolos Pyrgelis is a Post-Doctoral researcher at the Laboratory for Data Security of École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. His research interests include privacy-enhancing technologies and applied cryptography, and enjoys studying problems at the intersection of big data analytics and security or privacy. He received his PhD from University College London and his BSc and MSc from the University of Patras in Greece.

**Dr. Ioannis Krontiris holds a Ph.D. Degree in Computer Science from University of Mannheim in Germany, and a M.Sc. Degree in Information Technology from Carnegie Mellon University in USA, while he is also a graduate from the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering of the Technical University of Crete. He is currently working as a Privacy Engineer at the European Research Center of Huawei in Munich, Germany.

Online Shopping: Do we all pay the same price for the same product?

Written by Eirini Volikou*

On the same day, three people enter a book store looking to buy the book The secrets of the Internet. The book retails for €20 but the price is not indicated. The bookseller charges the first customer to walk in – a well-dressed man holding a leather briefcase and the new iPhone – €25 for the book. A while later a regular customer arrives. The bookseller knows that he is a student with poor finances and sells the book to him for €15. Finally, the third customer shows up; a woman who seems to be in a hurry to make the purchase. She ends up purchasing The secrets of the Internet at the price of €23. None of the customers is aware that each one paid a different price because the bookseller used information he deduced from their “profiles” to deduce their buying power or willingness.

In our capacity as consumers, how would we describe such a practice?

Is it fair or unfair, correct or wrong, lawful or unlawful?

And how would we react were we made aware that it targets us as well?

The above scenario may be completely fictitious but could it materialize in the real world?

In principle, the conditions in “regular” commerce are not such as to allow the materialization of our scenario. The obligation to clearly indicate the prices of products in brick and mortar stores directly and dramatically limits the traders’ freedom in charging prices higher than those indicated based on each individual client. In e-commerce, though, reality can prove to be strikingly similar to our fictitious scenario.

The e-commerce reality aka the “bookseller” is alive

Not infrequently it is observed that the indicated price of a good or a service on e-commerce platforms is not the same for everyone but divergences occur depending on the profile of the future customer.

Our online profiles are composed of information such as gender, age, marital status, type and number of devices we use to connect to the internet, geographical location (country or even neighborhood), nationality, preferences and consumer habits (history of searches or purchases) and so on.

This information is made known to the websites we visit via cookies, our IP address, and our user log-in information and can be used not only to show results and advertisements relevant to us but also to draw conclusions about our purchasing power or willingness. In other words, the role of the fictitious bookseller play algorithms that use our profiles for the purpose of categorizing us and automatically calculating and presenting to us a final price that we would be prepared to pay for the subject of our search.

This price may differ between users or categories of users who are often unaware of such categorisation or of the price they would be asked to pay had the platform had no access to their personal data.

This practice is often referred to as personalised pricing or price discrimination.

It is not to be confused with dynamic pricing in which the price is adjusted based on criteria that are not relevant to any individual customer but based on criteria relevant to the market, such as supply and demand.

The issue of personalized pricing surfaced in the public debate in the early 2000s when regular Amazon users noticed that by deleting or blocking the relevant cookies from their devices – which meant being regarded as new users by the platform – they could purchase DVDs at lower prices. The widespread use of e-commerce in combination with the rampant collection and processing of our personal data online (profiling, data scraping, Big Data) has since paved the way for the facilitation and spread of personalized pricing.

The experiment aka the “bookseller” in action

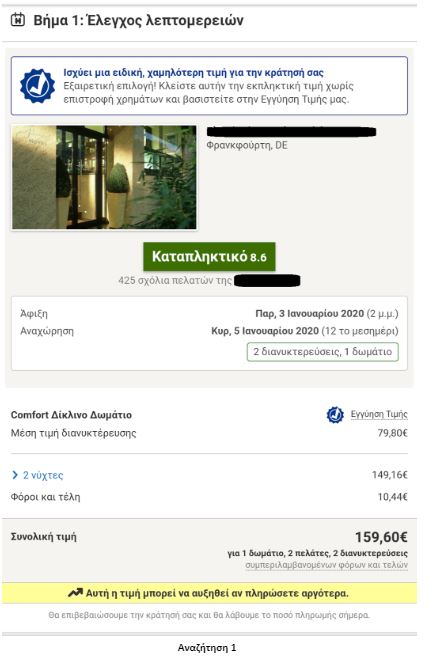

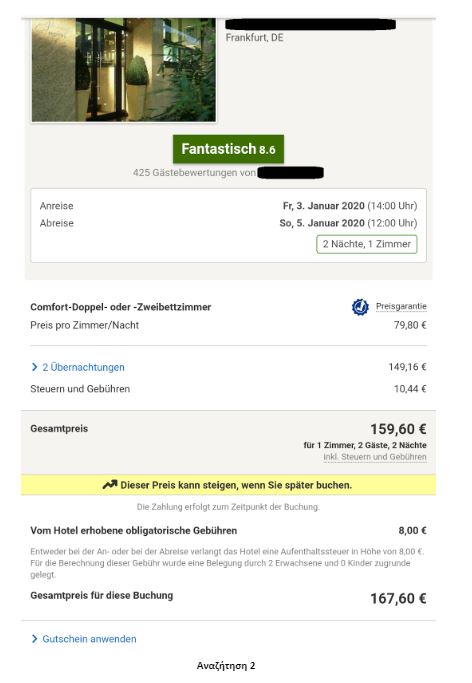

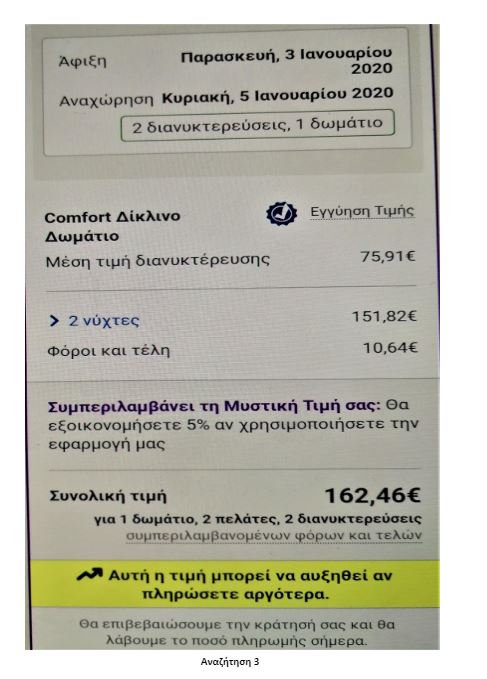

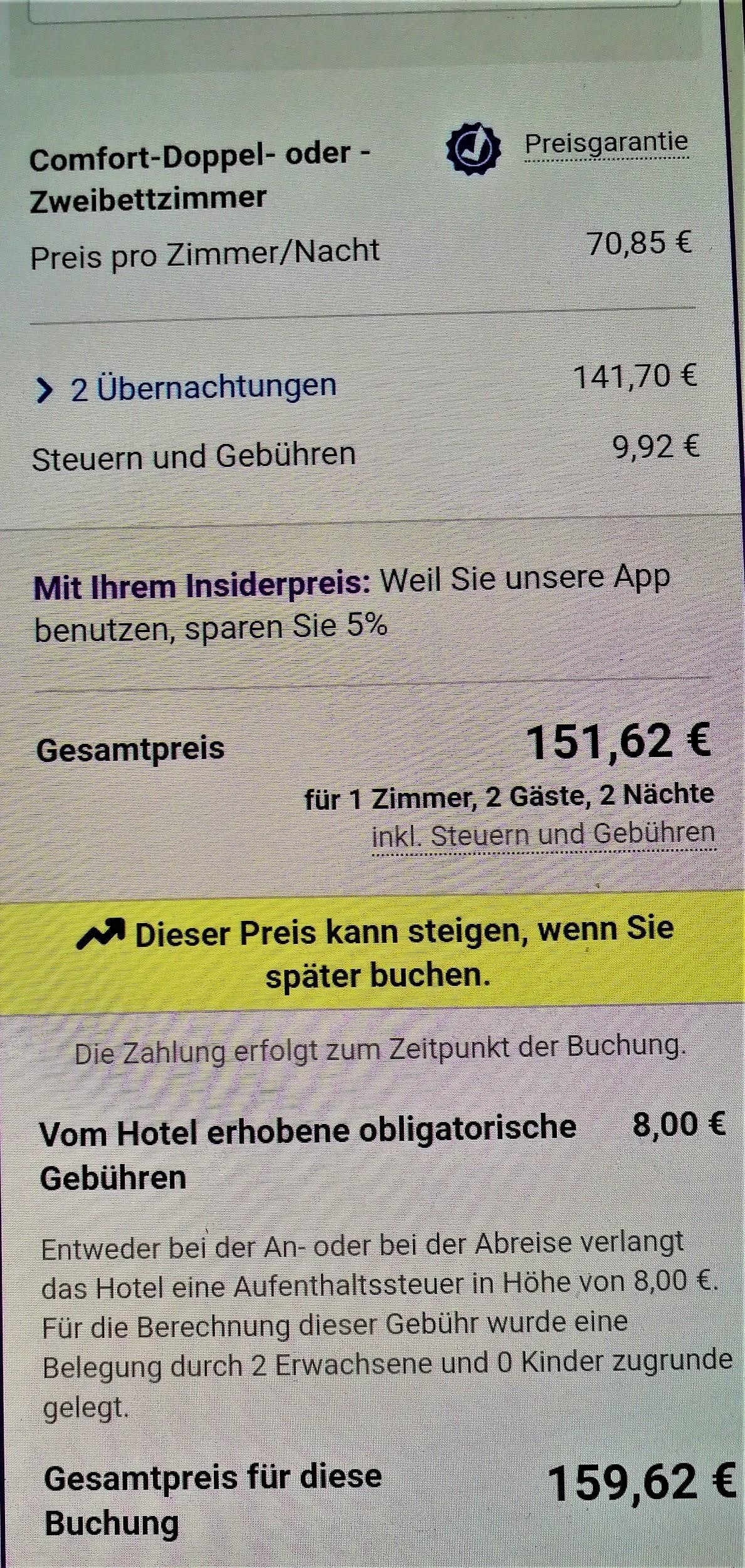

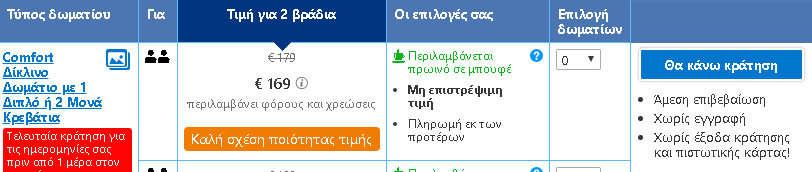

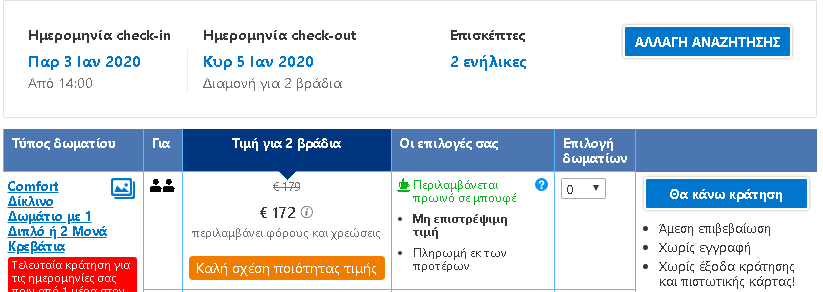

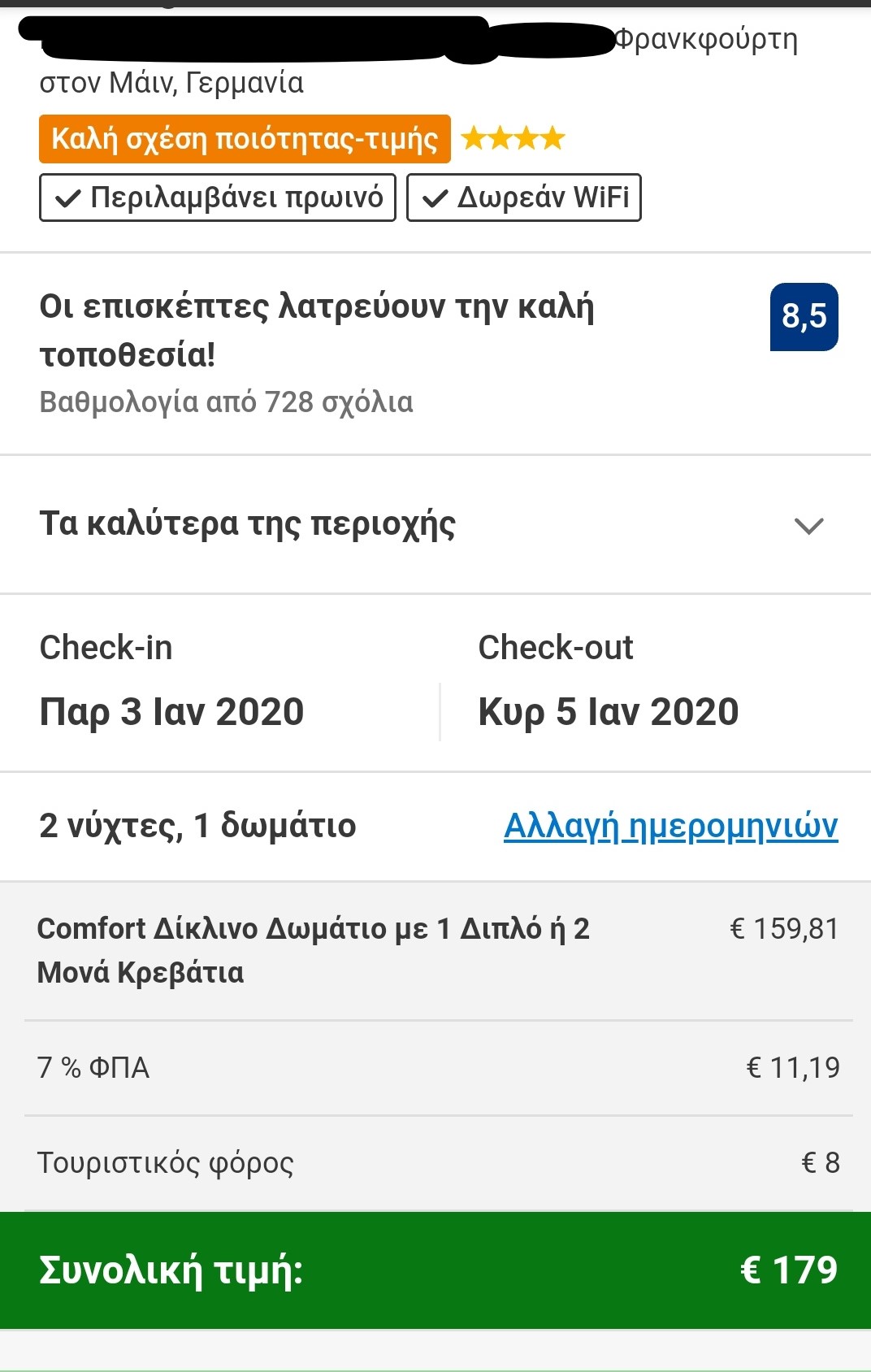

To put the practice to the test, consecutive searches and price comparisons were conducted on the same day (17/12/2019) for exactly the same room type (a “comfort” double room with one double or two twin beds) with breakfast for 2 travelers at the same hotel in Frankfurt, Germany on 3-5 January 2020. The searches were conducted on two different hotel booking websites and in all instances they reflect the lowest, non-refundable price option. The results are shown below:

Website Α

| Device | Browsing method | Website version | Price in € | |

| 1 | Τablet | Browser | Greek | 159,60 |

| 2 | Tablet | Browser | German | 167,60 |

| 3 | Tablet | Application | Greek | 162,46 |

| 4 | Tablet | Application | German | 159,62 |

Website Β

| Device | Browsing method | Website version | Price in € | |

| 5 | Laptop | Browser | Greek | 169,00 |

| 6 | Laptop | Incognito browser | Greek | 172,00 |

| 7 | Smartphone | Browser | Greek | 179,00 |

Search 1

Search 2

Search 3

Search 4

Search 5

Search 6

Search 7

The search results show a range of different prices for the same room on the same dates.

There is a noteworthy price divergence depending on the consumer’s country or location. Even for the same country, though, the prices differ considerably depending on the type of device combined with the browsing method used.

All this information – or even the lack thereof in the case of incognito browsing – appears to play a role in the final price calculation and, hence, in the customized pricing for the users.

How is personalized pricing dealt with?

Personalised pricing, arguably, brings advantages especially for consumers with low purchasing power who benefit from lower prices or discounts and can have access to products or services that they could otherwise not afford. However, consumer categorization and price differentiation give rise to concerns because they are processes mostly unknown to consumers and obscure as to the specific criteria they employ.

At the same time, the use of parameters like the ones that appeared to influence the price in the hotel room experiment, i.e. country/language, device, and browsing method, does not guarantee a classification of purchasing power that corresponds to reality. What is more, research has shown that consumers, when made aware of the application of personalized pricing, reject this practice by a majority as unfair or unacceptable. This is largely true also in the event that personalized pricing would benefit them if they were also made aware that such benefit requires the collection of their data and the monitoring of their online or offline behavior.

When it comes to the legal approach to personalised pricing, different fields of law are concerned by it.

In the framework of data protection law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) does not explicitly regulate personalized pricing. Nevertheless, it provides that should an undertaking be using personal data (including IP address, location, the cookies stored in a device, etc.) it is obliged to inform about the purposes for which they are being used.

It follows that, if consumer profiles are being used for the calculation of the final price of a good or service, this should, at the very least, be mentioned in the privacy policy of the e-commerce platform.

The GDPR also requires consumer consent if personalized pricing has been based on sensitive personal data or if personal data is used in automated decision-making concerning the consumer.

From a consumer protection law perspective, traders can, in principle, set the prices for their goods or services freely insofar as they duly inform consumers about these prices or the manner in which they have been calculated. Personalized pricing could be prohibited if applied in combination with unfair commercial practices provided for in the text of the relevant Directive 2005/29/EC.

However, recently adopted Directive (EU) 2019/2161, which aims to achieve the better enforcement and modernization of Union consumer protection rules, will hopefully contribute to limiting consumer uncertainty and improving their position.

With the amendments that this Directive brings about not only is personalized pricing recognized as a practice but also the obligation is established to inform consumers when the price to be paid has been personalized on the basis of automated decision-making so they can take the potential risks into consideration in their purchasing decision (Recital 45 and Article 4(4) of the Directive). The Directive was published in the Official Journal of the EU on 18/12/2019 and the Member States should apply the measures transposing it by 28/5/2022.

It should be noted, albeit, in brief, that personalized pricing is an issue that competition law is also concerned with and, in particular, the possibility of charging higher prices to specific consumer categories for reasons not related to costs or for utilities by firms that hold a dominant position in a market.

In any case, staying protected online is also a personal matter.

At the Roadmap to Safe Navigation (in Greek) issued by Homo Digitalis, there can be found the behaviors we can adopt to protect our personal data while navigating through the Internet.

Consumers can adopt behaviors that help protect their personal data while browsing, such as using a virtual private network (VPN), opting for browsers and search engines that do not track users and using email and chat services that offer end-to-end encryption. To deal with personalized pricing, in particular, thorough market research, price comparison on different websites, or even different language versions of a single website, trying different browsing methods and, if possible, different devices can be a good start. It is important for e-commerce users to stay informed and alert in order to avoid having their profile used as a tool towards charging higher prices.

*Eirini Volikou, LL.M is a lawyer specializing in European and European Competition Law. She has extensive experience in the legal training of professionals on Competition Law, having worked as Deputy Head of the Business Law Section at the Academy of European Law (ERA) in Germany and, currently, as Course Co-ordinator with Jurisnova Association of the NOVA Law School in Lisbon.

SOURCES

1) European Commission – Consumer market study on online market segmentation through personalized pricing/offers in the European Union (2018)

2) Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules

3) Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market and amending Council Directive 84/450/EEC, Directives 97/7/EC, 98/27/EC and 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council (‘Unfair Commercial Practices Directive’)

4) Commission Staff Working Document – Guidance on the implementation/application of Directive 2005/29/EC on unfair commercial practices [SWD(2016) 163 final]

5) Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)

6) Poort, J. & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2019). Does everyone have a price? Understanding people’s attitude towards online and offline price discrimination. Internet Policy Review, 8(1)

7) OECD, ‘Personalised Pricing in the Digital Era’, Background Note by the Secretariat for the joint meeting between the OECD Competition Committee and the Committee on Consumer Policy on 28 November 2018 [DAF/COMP(2018)13]

8) BEUC, ‘Personalised Pricing in the Digital Era’, Note for the joint meeting between the OECD Competition Committee and the Committee on Consumer Policy on 28 November 2018 [DAF/COMP/WD(2018)129]9) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/914691.stm

Homomorphic Encryption: What is and Known Applications

Written by Anastasios Arampatzis

Every day, organizations handle a lot of sensitive information, such as personal identifiable information (PII) and financial data, that needs to be encrypted both when it is stored (data at rest) and when it is being transmitted (data in transit). Although modern encryption algorithms are virtually unbreakable, at least until the coming of quantum computing, because they require too much processing power too break them that makes the whole process too costly and time-consuming to be feasible, it is also impossible to process the data without first decrypting it. And decrypting data, makes it vulnerable to hackers.

The problem with encrypting data is that sooner or later, you have to decrypt it. You can keep your cloud files cryptographically scrambled using a secret key, but as soon as you want to actually do something with those files, anything from editing a word document or querying a database of financial data, you have to unlock the data and leave it vulnerable. Homomorphic encryption, an advancement in the science of cryptography, could change that.

What is Homomorphic Encryption?

The purpose of homomorphic encryption is to allow computation on encrypted data. Thus data can remain confidential while it is processed, enabling useful tasks to be accomplished with data residing in untrusted environments. In a world of distributed computation and heterogeneous networking this is a hugely valuable capability.

A homomorphic cryptosystem is like other forms of public encryption in that it uses a public key to encrypt data and allows only the individual with the matching private key to access its unencrypted data. However, what sets it apart from other forms of encryption is that it uses an algebraic system to allow you or others to perform a variety of computations (or operations) on the encrypted data.

In mathematics, homomorphic describes the transformation of one data set into another while preserving relationships between elements in both sets. The term is derived from the Greek words for “same structure.” Because the data in a homomorphic encryption scheme retains the same structure, identical mathematical operations, whether they are performed on encrypted or decrypted data, will result in equivalent results.

Finding a general method for computing on encrypted datahad been a goal in cryptography since it was proposed in 1978 by Rivest, Adleman and Dertouzos. Interest in this topic is due to its numerous applications in the real world. The development of fully homomorphic encryption is a revolutionary advance, greatly extending the scope of the computations which can be applied to process encrypted data homomorphically. Since Craig Gentry published his idea in 2009, there has been huge interest in the area, with regard to improving the schemes, implementing them and applying them.

Types of Homomorphic Encryption

There are three types of homomorphic encryption. The primary difference between them is related to the types and frequency of mathematical operations that can be performed on the ciphertext. The three types of homomorphic encryption are:

- Partially Homomorphic Encryption

- Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption

- Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Partially homomorphic encryption (PHE) allows only select mathematical functions to be performed on encrypted values. This means that only one operation, either addition or multiplication, can be performed an unlimited number of times on the ciphertext. Partially homomorphic encryption with multiplicative operations is the foundation for RSA encryption, which is commonly used in establishing secure connections through SSL/TLS.

A somewhat homomorphic encryption (SHE) scheme is one that supports select operation (either addition or multiplication) up to a certain complexity, but these operations can only be performed a set number of times.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), while still in the development stage, has a lot of potential for making functionality consistent with privacy by helping to keep information secure and accessible at the same time. It was developed from the somewhat homomorphic encryption scheme, FHE is capable of using both addition and multiplication, any number of times and makes secure multi-party computation more efficient. Unlike other forms of homomorphic encryption, it can handle arbitrary computations on your ciphertexts.

The goal behind fully homomorphic encryption is to allow anyone to use encrypted data to perform useful operations without access to the encryption key. In particular, this concept has applications for improving cloud computing security. If you want to store encrypted, sensitive data in the cloud but don’t want to run the risk of a hacker breaking in your cloud account, it provides you with a way to pull, search, and manipulate your data without having to allow the cloud provider access to your data.

Applications of Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Craig Gentry mentioned in his graduation thesis that “Fully homomorphic encryption has numerous applications. For example, it enables private queries to a search engine – the user submits an encrypted query and the search engine computes a succinct encrypted answer without ever looking at the query in the clear. It also enables searching on encrypted data – a user stores encrypted files on a remote file server and can later have the server retrieve only files that (when decrypted) satisfy some boolean constraint, even though the server cannot decrypt the files on its own. More broadly, fully homomorphic encryption improves the efficiency of secure multi party computation.”

Researchers have already identified several practical applications of FHE, some of which are discussed herein:

- Securing Data Stored in the Cloud. Using homomorphic encryption, you can secure the data that you store in the cloud while also retaining the ability to calculate and search ciphered information that you can later decrypt without compromising the integrity of the data as a whole.

- Enabling Data Analytics in Regulated Industries. Homomorphic encryption allows data to be encrypted and outsourced to commercial cloud environments for research and data-sharing purposes while protecting user or patient data privacy. It can be used for businesses and organizations across a variety of industries including financial services, retail, information technology, and healthcare to allow people to use data without seeing its unencrypted values. Examples include predictive analysis of medical data without putting data privacy at risk, preserving customer privacy in personalized advertising, financial privacy for functions like stock price prediction algorithms, and forensic image recognition.

- Improving Election Security and Transparency. Researchers are working on how to use homomorphic encryption to make democratic elections more secure and transparent. For example, the Paillier encryption scheme, which uses addition operations, would be best suited for voting-related applications because it allows users to add up various values in an unbiased way while keeping their values private. This technology could not only protect data from manipulation, it could allow it to be independently verified by authorized third parties

Limitations of Fully Homomorphic Encryption

There are currently two known limitations of FHE. The first limitation is support for multiple users. Suppose there are many users of the same system (which relies on an internal database that is used in computations), and who wish to protect their personal data from the provider. One solution would be for the provider to have a separate database for every user, encrypted under that user’s public key. If this database is very large and there are many users, this would quickly become infeasible.

Next, there are limitations for applications that involve running very large and complex algorithms homomorphically. All fully homomorphic encryption schemes today have a large computational overhead, which describes the ratio of computation time in the encrypted version versus computation time in the clear. Although polynomial in size, this overhead tends to be a rather large polynomial, which increases runtimes substantially and makes homomorphic computation of complex functions impractical.

Implementations of Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Some of the world’s largest technology companies have initiated programs to advance homomorphic encryption to make it more universally available and user-friendly.

Microsoft, for instance, has created SEAL (Simple Encrypted Arithmetic Library), a set of encryption libraries that allow computations to be performed directly on encrypted data. Powered by open-source homomorphic encryption technology, Microsoft’s SEAL team is partnering with companies like IXUP to build end-to-end encrypted data storage and computation services. Companies can use SEAL to create platforms to perform data analytics on information while it’s still encrypted, and the owners of the data never have to share their encryption key with anyone else. The goal, Microsoft says, is to “put our library in the hands of every developer, so we can work together for more secure, private, and trustworthy computing.”

Google also announced its backing for homomorphic encryption by unveiling its open-source cryptographic tool, Private Join and Compute. Google’s tool is focused on analyzing data in its encrypted form, with only the insights derived from the analysis visible, and not the underlying data itself.

Finally, with the goal of making homomorphic encryption widespread, IBM released its first version of its HElib C++ library in 2016, but it reportedly “ran 100 trillion times slower than plaintext operations.” Since that time, IBM has continued working to combat this issue and have come up with a version that is 75 times faster, but it is still lagging behind plaintext operations.

Conclusion

In an era when the focus on privacy is increased, mostly because of regulations such as GDPR, the concept of homomorphic encryption is one with a lot of promise for real-world applications across a variety of industries. The opportunities arising from homomorphic encryption are almost endless. And perhaps one of the most exciting aspects is how it combines the need to protect privacy with the need to provide more detailed analysis. Homomorphic encryption has transformed an Achilles heel into a gift from the gods.

This article was originally published on the Venafi blog at: https://www.venafi.com/blog/homomorphic-encryption-what-it-and-how-it-used.

Reparations for immaterial damage under the GDPR: A new context

Written by Giorgos Arsenis*

A court in Austria sentenced a company to 800 Euros of compensation-payment towards a data-subject, for reasons of immaterial (emotional) harm, according to article 82 of the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). The verdict is not in force yet, since both parties have appealed the decision, but in case the verdict will remain unchanged in the second instance, then the company might be facing a mass lawsuit, where about 2 million data-subjects are involved.

The case has gained momentum since its outcome will constitute a legal paradigm, upon which future cases will be based. But let’s take a step back and have a broader look at this verdict and the consequences this application of article 82 might have towards the justice systems of other members of the European Union.

Profiling

The fact that a Post Office gathers and saves personal data of its customers is nothing new. But after a data-subject’s request, it was revealed that Austria’s Post, allegedly, evaluated and stored data that concerned the political preferences of approximately 2 million of its clients.

The said company used statistical methods such as profiling, aiming to estimate the level of affinity of a person towards an Austrian political party (e.g. significant possibility of affinity for party A, insignificant possibility of affinity for party B). According to media, it appears that none of the customers had provided their consent for this processing activity and in certain cases that information was acquired by further entities.

Immaterial harm has a price

The local court of Feldkirch in Voralberg, a confederate state of Austria bordering with Lichtenstein, where the hearing took place in the first instance, ruled that the sheer feeling of distress sensed by the claimant due to the profiling he was subjected to without his consent, constitutes immaterial harm. Therefore, the accuser was awarded 800 Euros, from the 2.500 Euros he claimed initially.

The court acknowledged that the political beliefs of a person are a special category of personal data, according to article 9 of GDPR. However, it also acknowledged that every situation perceived as unfavorable treatment, cannot give rise for compensation claims based on moral damages. Nevertheless, the court concluded that in this case, fundamental rights of the data-subject had been violated.

The calculation of the compensation was based on a method that applies in Austria. In line with that method, the court took two main elements into account: (1) that political opinions are an especially sensitive category of personal data and (2) that the processing activity was conducted without the awareness of the data-subject.

And now?

The verdict is no surprise. Article 82 § 1 of the GDPR clearly foresees compensation payment for immaterial harm. However, with 2,2 million data-subjects affected from this processing activity and simply by doing the math, what derives is the amount of 1,7 billion Euros. Certain is, that if the court of appeal confirms the decision, there will be a plethora of similar cases for litigation. This is the reason why already, in neighbouring Germany, many companies specialize in cases like this.

The Independent Authority

After the decision of the local court in Feldkirch in the beginning of October 2019, towards the end of the same month (29.10.2019) the Austrian Data Protection Authority (Österreichische Datenschutzbehörde), announced that an administrative sanction of 18 million Euros was imposed to the Austrian Postal Service. Beyond political beliefs, the independent authority detected more violations. Via further processing, evidence about the frequency of package deliveries or residence change were obtained, which were used as means for direct-marketing advertisement. The Austrian Postal Service, which by half belongs to the state, reported that it will take legal action against this administrative measure and justified the purpose of the processing activities as legitimate market analysis.

What makes the verdict distinctive

The verdict in Feldkirch shows that the courts are able to impose fines for certain “adversities” caused by real or hypothetical violations of personal data.

Unlike the independent authority, that imposed the administrative sanction due to multiple violations of the GDPR-clauses, the local court in Feldkirch focused on the ‘disturbance’ sensed by the complainant.

The complainant simply stated that he ‘felt disturbed’ for what happened, i.e. without pleading a moral damage resulting from the processing activity, such as defamation, copyright abuse or harassment by phone calls or emails. The moral damage was induced by the fact that a company is processing personal data in an unlawful manner.

You can find the decision here.

* Giorgos Arsenis is an IT Consultant και DPO. He has long-standing experience in IT Systems Implementation & Maintenance, in a number of countries in Europe. He has been active for agencies and institutions of the EU and in the private sector. He is qualified in servers, networks, scientific modelling and virtual machine environments. Freelancer, specializes on Information Security Management Systems and Personal Data Protection.

Digital Sources:

Interview with the Senior Director Government Affairs of Symantec, Ilias Chantzos

His title merely impresses: “Senior Director Government Affairs EMEA and APJ, Global CIP and Privacy Advisor” for Symantec, a leader company in the Cybersecurity sector.

In other words, Mr Ilias Chantzos is the person responsible for the intergovernmental relations of Symantec for almost every state of the globe (apart from America), regarding Cybersecurity and data protection issues. Symantec, is one of the leading companies of Cyber Security software worldwide, with hundreds of millions users.

After all, who is not familiar with ‘Norton Internet Security’, Symantec’s most popular and No 1 product for customer protection?

Our first contact was at Data Privacy & Protection Conference where he vividly presented the topic of security breaches and the notification of such breaches. We kindly asked him to share his views on the contemporary developments on the sector as well as the role of NGOs. Despite his busy schedule, he ardently accepted our invitation. We thank him thus, for this extremely interesting interview.

In Greece, entire generations have been brought up in the framework of ‘Rightsism’ and ‘politically correctness’ Τhe crisis we experience is both economical as well as moral.

– HD:The implementation of GDPR and NIS renders Europe as a pioneer in the creation of an integrated, prescriptive setting for Cybersecurity and data protection. What are the next steps?

IC: Initially, the first step is the full implementation of GDPR. And this will become viable through the adaptation of individual rules, such as the guidelines set by the European Data Protection Board (EBPB), the imposition of fines functioning as impediments to the non abidant organisations and through solving issues arising from data transmission, especially to America. The latter acting as a sticking point to mutual interests of great, private companies.Then, adequacy decision with other countries, such as Korea will follow, which will eventually create a great secure flow space and, of course, the final decisions regarding e-privacy Regulation.

-HD: On that occasion, let me ask you about the efforts and the enormous funds that are allegedly spent within lobbying settings from giants in the technology sector such as Google and Apple on favorable e-privacy conformation towards them.

ΙC: Well, isn’t it reasonable for the companies to be interested about rules that concern and directly regulate them? The industry’s interests are not common, rather than different and dissenter. If, for example, a regulatory context is favorable for company X, the same context will be less favorable for company Y which operates in a similar but not the same sector. The same happens with e-privacy.

Companies are ‘fighting’ each other because their interests are not common. Ιn Greece there is neither the conscience nor the full picture of the entrepreneurship interest due to the demonising of profit and entrepreneurship that emerges from the past’s ideological stiffness. We should not face the industry as a caricature of a bad capitalist, but realistically through the prism of complicated relations and existing interests. Τhis is the only way that bodies will perform correctly. Let’s give an example that everyone in Greece will easily understand. The legislature regarding dual tanks in sea-going tankers is supposed to protect the environment from oil leaks. This type of legislature is supported by environmental NGOs and shipyards (an industry that mostly pollutes. . . Can you spot the paradox already?) because it can be translated into brand new orders. Ιt will be supported by the coastal states of European Union but it is not useful to Greece (which has the greatest coastline and tremendous tourism), which has mostly sea-going shipping since it augments its costs while having zero income from its shipping.

Can you spot how many contradictions there are in one simple example and we haven’t even discussed about local communities that have suffered sea contamination and the tourism industry.

-HD: You mentioned fine imposition earlier. Recently, we watched huge companies such as Google, British Airways and Marriott being imposed tremendous fines leaving everyone believing that no one is immune within the Cybersecurity and protection of privacy sector. Thus, if the ultimate protection and secure processing of personal data is impossible, then what is at stake here? Why all this is happening?

IC: In the companies that you mentioned, fines were imposed for different reasons. Regarding the Google case, fines were imposed for lawfulness of data processing , and more specifically their collection and processing, whereas in Marriott and British Airlines cases fines were imposed due to restricted data protection measures. There is no absolute security to anything in life, the same stands for security. The authorities though, did evaluate that those companies should have protected data much more attentively. Unfortunately, that was not applied this way and this is the reason that fines were imposed, indicating that privacy protection is a top priority.

-HD: In Greece, why do you believe that fines are not equally high?

IC:There are many factors implicated.Up to date greek companies invested in highly essentials. In state of economic crisis you do what is necessary to ensure smooth operation. Current fines are calling for the national companies which want to sell products and services abroad to answer a critical question that every foreign client will ask: “ Can you protect my personal data effectively? ”. Ι understand that small and medium sized enterprises comprehend security mainly as a cost. It is like car insurance which you may never use.

Nevertheless, security can become a competitive advantage. Even if we are kind of left behind, middle sized enterprise should keep up and improve its products and services quality. Quality will make you competitive. I understand that this quality might increase your cost but you belong in the European Union. You have to play according to these rules!

-HD: How do you perceive the NGOs role in this sector? What would you advise an organisation such as Homo Digitalis in order to make their action more effective?

Do not act as ‘rightsists’. In Greece, entire generations have been brought up in the framework of ‘Rightsism’ and ‘politically correctness’ Τhe crisis we experience is both economical as well as moral.This, of course, does not mean we have to stop fighting for our rights. We ought though, with every enquiry that we make to be well informed of its losses and its gains.Which are the consequences of our choices. Not blindly ask just because we can.

It’s the so called ‘occassional cost’. Namely, you should be informed as far as possible which are the other options, that you rejected, before the finally chosen. It is not possible, for example, based on the current business model, to ask for free internet without accepting advertisements (it should be noted that I do not like them).

You don’t like advertisements? No problem, can you afford to pay for the service you receive or to ensure the share of privacy you want? Ιt’s not enough to ask. You also have obligations. Unfortunately, we are victims of the trend “I need X at all costs”, without having thought what we lose or what we accept. It is indicator of maturity and resistance to populism to be able to distinguish easy rightsism from the one that is really in our interest. This is the biggest challenge in my opinion for all NGOs.

How to create and use powerful passwords

Written by Vyron Kavalinis *

On the web, it is widespread that a website needs the user’s registration to display its content or provide its service or even allow to comment on an article. The registration of the user, and consequently, the account creation requires the use of a username and a password.

The username will need to be unique and no longer linked to the page itself to create the required account while the username and password combination proves the user’s identity and the correct completion give them access to the content of your page. Even in our email, if we want to sign in we will need a username (usually our email address) and a password.

The password is usually a combination of letters, symbols and numbers. The use of strong passwords is necessary to protect the user’s security and identity. An easy password is more likely to be guessed by someone else and therefore has access to our personal data.

Initially, an easy password is short. The bigger the password is, the harder is to be guessed by someone, and the resulting combinations are much more. From researches into millions leaked passwords, it has been revealed that combinations and selections preferred by users are very easy and are in the form “123456”, “password”, “football” and other simple words that we all use in our everyday life, and it is therefore easy for a third person to guess and find.

It is also worth mentioning the fact that a large number of users use the same password on all the pages they need to link. So if someone knows our email or our username then with a single password they can have access to all the pages we have an account, whether this page is our bank’s account or a shop that we are buying or even our own profile on Facebook.

The best way to increase security levels is to create more complex passwords. It is recommended that the password be long, usually over 12 characters, and be sentences that the user can easily remember.

A good way is the use of Online tools, which add words at random and create sentences for their use as passwords or setting up codes in accordance with some options determined by the user. In the text that follows we shall refer to some examples of such tools that you can use.

It is worth mentioning that a password with at least 12 characters can take few centuries for an invader to break it. In the current computer capacities and with the simultaneous use of many of them, this time might not be actual but still is so much to break. For example, according to researches that have been carried out, a supercomputer (having an efficiency as 100 computers at the same time) can break a 10-character password in 3 years.

It is not recommended to use the same password in every web site and application as also to not write down the passwords on simple text files or notebooks.

Moreover, the use of symbols and numbers can really help as the password becomes more complicated and therefore more difficult for a third person to find it.

The use of password generators is a very good solution since the most enable the user to set the parameters of the password and to create one, ready for use. Generators’ use is very helpful as if necessary for a web site to use capital symbols and small will create a more complex password. For example in that case a human would allocate a password “Letmein!123”, while a password generator would allocate “lwIXgHeaWiq”. The second choice is more difficult to find even if it doesn’t include special characters and symbols.

The use of password generators doesn’t require specific and specialised knowledge from the user, while there are many online tools that can be used for the creation of our passwords. We can show you online password generators that you can use:

Strong password generator (https://www.strongpasswordgenerator.com/). It gives the opportunity to define the length of the code and also some options of configuration, like the use of “voice words”. With the use of voice words actually the generator shows the letter and number combination in words so the passwords be more memorable.

Norton Password Generator (https://my.norton.com/extspa/idsafe?path=pwd-gen|). Norton, known in the field of safety has set up an online tool for the creation of passwords. This specific tool gives many options as the choice of the length of the code and the use of capitals, symbols and numbers.

XKpassword (https://xkpasswd.net/s/). XKpassword is probably one of the few, who offer so many options for the creation of the password. A feature differentiating it from the majority of password generators is the selection of provider according to the rules of which the password will be created. Some of these examples are according to the frameworks of AppleID, WiFi etc.

Finally, we would recommend the use of password managers for the storage and the management of your passwords. Password managers are substantially programs, which manage your passwords and store them coded in order to be understood by someone other. Through the use of this programs you just need to know one password and this is your access code to your password manager.

With the use of password managers you don’t have to remember your passwords by heart, as they have addons for every known browser, that when you enter to a web site they immediately recognise through the relevant form and give you the possibility of automatic completing.

Some password managers, also authorise the automatic completion with random passwords when registering and their automatic storage.

Since there is the possibility for somebody to intercept the password from the password manager and therefore to have access to the others, many from password managers provide also extra safeguards in the event of unusual mobility.

One of the most well-known password managers is the LastPass and the 1Password. Both provide the possibility of free use, while upon payment subscription they unlock more options and functions. Both have admins for Chrome, Mozilla, Opera and operate with Windows, Linux and MacOS. It is also noteworthy that if you take notice that your main code has been intercepted you can request for your account to be deleted, while 1Password recognises the device with which you are connecting and if you wish to connect from a new one you have to complete the master password you have been given after your registration to the application automatically.

We shall mention that there have been notified various safety lapses in password managers. Despite all these, each and every company immediately takes all the necessary steps to fill these gaps and increase the safety of their services. Even after of those notifications their use is considered to be more safe than the storage of passwords within a simple file, which will not contain any type of encryption.

Homo Digitalis has no interest in suggesting the above tools. We recommend you use these tools as safe alternatives given the wide variety of such tools. It shall be noted that many of these tools might have as objective to intercept your data. Therefore, we recommend you be very careful when you are using such tools.

* Viron is a graduate from the Department of Informatics Engineering, TEI Crete. He works for a company, which operates in the field of Web hosting and domain names. He deals with the development of web sites and safety. In the past he has undertaken SSL certificates.