European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet): The Uncomfortable Truth Behind the Innovation

By Giannis Konstantinidis*

Note: This is the English translation of the original article which was written in Greek.

A critical look at the EU’s new “wallet” and the hidden risks it poses to personal data protection and privacy in the digital age.

What are digital identities?

Digital identities are the set of information (e.g. name, professional status, address, telephone number, password) that characterise us when we use digital services on the Internet. In simple words, they are our “digital selves” when we connect to social networking platforms, e-government services, e-banking systems, etc. In practice, digital identities contain personal data which in many cases are also sensitive (e.g. in the case of e-health services). Therefore, digital identities must enable fast and trouble-free access to digital services and meanwhile be accompanied by strict safeguards regarding information security and data protection.

How have digital identities evolved?

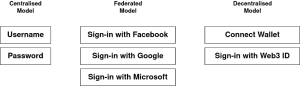

There are three main models for organising digital identities (Figure 1). In the centralised model, an organisation maintains a central database with the digital identities of all users. A key disadvantage of the centralised model is that users must maintain a separate account for each digital service they use. In contrast, in the federated model, organisations cooperate with each other and exchange digital identity information using a common protocol. For example, if a user has an account with a central provider (e.g. Facebook, Google, Microsoft or gov.gr), then they can log-in to another compatible digital service with the same information. Therefore, the federated model is quite easy to use, although the overall management of digital identities and their attributes is carried out by a few providers (who might be aware of the users’ activities).

Figure 1: In the centralised model, users have separate accounts (and passwords) for each service they use. In contrast, in the federated model, there are a few providers that act as single “gateways” to services. Finally, in the decentralised model, users use their digital wallets and ideally choose the specific information they want to share with service providers. (Creator Giannis Konstantinidis)

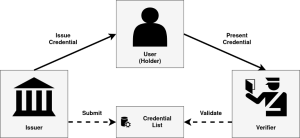

Therefore, in both the centralised and the federated model, a major concern is the concentration of a large amount of data in central locations that are considered attractive to malicious attackers (see massive data breaches). As an “antidote”, the decentralised model has been proposed, which is often associated with the concept of “self-sovereign identity” (SSI). In this model, the user controls all the identity elements that are to be used by the services. Instead of relying upon a few providers, each user holds a set of “credentials”, which have been issued by trusted entities, and maintains them in an application called a digital wallet or digital identity wallet. When the user needs to prove something (e.g. their age), the digital credential is directly presented (signed beforehand by a trusted organisation that serves as the issuer). Ideally, the presentation of that digital credential reflects the minimum amount of the required data and does not reveal the entire personal data of the user.

Figure 2: In the decentralised model, the issuer generates and delivers a credential to the user (holder) who stores it in the digital wallet. The user then presents the credential to a verifier, i.e. an organisation that requests confirmation of the user’s identity and/or status. The validity of the credential is verified based on the information found in a registry.(Creator Giannis Konstantinidis)

What is happening in the EU with digital identities?

With the revision of the eIDAS Regulation (2024/1183), the European Commission has established that each EU Member-State must offer its citizens a digital identity wallet. This will be an application for mobile devices in which each user will be able to store documents in digital form (e.g. ID cards, driving licenses, educational qualifications, social security documents and other travel documents). The user's interaction with the respective services will be done through the wallet, i.e. the user will select the credentials they wish to share. As mentioned earlier, the entire documents are not sent by each user, but a selected presentation of certain data in combination with the appropriate digital evidence that cryptographically proves the validity of those documents. Admittedly, the original vision of a “sovereign identity” seems to be significantly limited in the current design of the EUDI Wallet. In particular, the draft architecture (i.e. Architecture and Reference Framework - ARF) foresees the use of a traditional Public Key Infrastructure (PKI). Simply put, instead of leveraging a fully decentralised system, the European Commission chooses to leverage existing infrastructures that collect digital identity data. As such, it is more of a cross-border federated model in which users are responsible for managing and sharing their credentials on their own, rather than a fully decentralised model.

Is the protection of privacy and personal data enhanced or undermined?

Based on current developments, several risks related to data protection and privacy arise. First, the wallet can generate unique identifiers for each user (although theoretically this is necessary to identify the user when accessing cross-border services in the EU) and several experts express fear that these identifiers will allow for the continuous monitoring and correlation of all user activities.

In particular, according to the position of a group of distinguished academics (specialists in cryptography), the proposed architecture does not include sufficient technical measures to limit the “observability” and prevent the “linkability” of user activities. This means that even if user activities are carried out through the use of pseudonyms, there is no special care to prevent service providers from collecting usage patterns and correlating them with each other. So, in practice, this gap allows the tracing of user activities. The latest version of the architecture (ARF 2.3.0) recognises these risks, however, the integration of appropriate mechanisms remains at the level of discussion and has not yet been implemented (due to complexity and certain technical limitations). The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) recognises the importance of technical measures, such as zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), but it is shown that (for the time being) the complete elimination of tracking is not feasible due to the technical complexity and lack of interoperability.

Regarding the overall “flexibility” and accountability of the ecosystem, there are also several negative comments. For example, if a service decides to request more data than necessary, there is no mechanism for prevention or even control. At the same time, it is considered that a huge share of responsibility will be shifted to users, because they will be constantly asked to approve the credentials that will be shared with service providers. In fact, if something goes wrong (e.g. in the event of theft of the user’s device or electronic fraud), there are no sufficient protection measures and therefore the user bears a large share of the responsibilities. In fact, there is no provision (so far) for any kind of recovery or restoration process.

Finally, an additional concern relates to the expansion of the wallet's functionalities, as it is going to gradually collect all kinds of electronic documents and certificates (e.g. even travel credentials and electronic payment details). Thus, the risk of a "surveillance dossier" emerges, where a malicious analyst or attacker could discover an extensive set of information about a person through a single medium.

Towards a cautious acceptance or questioning of the framework?

Although the EUDI Wallet is an important step in the development of modern digital services on the Internet, it comes with several challenges. If citizens are to trust such a technological solution, they must do so with full awareness of the advantages as well as the potential risks involved. At the same time, experts must further develop and document the mechanisms that contribute to security and privacy, otherwise we risk moving from a “wallet that empowers users to protect their data” to a “wallet that exposes data arbitrarily”. Finally, the contribution of experts and civil society organisations is extremely important, as gaps and possible omissions can be identified and corrected before the final implementation.

*Giannis Konstantinidis (CISSP, CIPM, CIPP/E, ISO/IEC 27001 & 27701 Lead Implementer) is a cybersecurity consultant and member of Homo Digitalis since 2019.